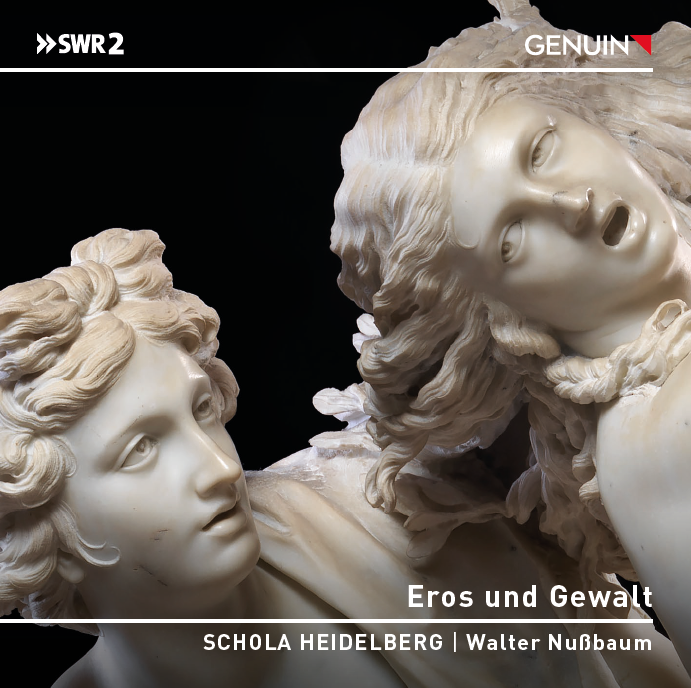

Eros and Violence

CD project: Five-part madrigals & chants for seven female voices

CD “Eros and Violence” - order now at: info@klanghd.de

Under the sign of Eros and Violence, sung by SCHOLA HEIDELBERG under Walter Nußbaum, works of vocal music encounter each other and their poetic basis, Italian madrigal poetry recited by actor Michael Rotschopf. But verses and songs meet on more than one level, for sung language is more than the linear sequence of its words and texts and far more than the catalogue of emotions of a lyrical ego or a composing subject.

The lives and deaths of the two composers Don Carlo Gesualdo da Venosa (1566–1613) and Claude Vivier (1948–1983) seem to have been marked by violence in one way or another: Gesualdo is believed to have commissioned a murder out of jealousy or honor, while Vivier was the victim of a murder motivated by greed, desperation, or passion. But what do we want to hear about this, what can we only read, what do we want to know? Must we understand “morte” literally as death, or, as a mannerism-addicted elite audience around 1600 could, metaphorically as a description of lust and sexual fulfillment—piece by piece, madrigal by madrigal? How morally pure (or impure) can these madrigals appear to us as recited, “pure text,” between their music, and how foreign in the sound of semi-familiar Italian? In his music for female voices, simply called Chants, Claude Vivier deconstructs and reconstructs language itself from fragments of dreams, splinters of thought, requiem consolation, and Catholic Marian mysticism, perhaps not without traces of Eros and violence. For him, his work is a “ritual of rebirth,” but we also know that music never allows, nowhere does this music or that of the madrigalists allow, the complete decoding and identification of a lyrical self. And how misguided it would be to try to morally distinguish Gesualdo's music from that of his ethically more unremarkable but aesthetically hardly more conventional contemporary Michelangelo Rossi (1601–1656) beyond the social conventions and codes of honor of their time – unless it be by way of listening.

Alongside Rossi (but also alongside Vivier), Gesualdo's emotionally charged and chromatic harmonies, which have challenged and inspired countless contemporary composers since Igor Stravinsky, may not prove to be so solitary after all – and, together with Rossi, may now call into question a supposed certainty of our musical practice: the overly black-and-white keyboard picture of equal temperament and exactly equal tuning ratios, gray on gray, chord after chord. In the colorful chromaticism of these madrigals, however, no two chords are alike. Just as no emotion, no human being, no life, and no death are alike. Neither Vivier's nor Gesualdo's music demands a direct biographical attribution. Their levels form and remain a large field of relationships: as a biotope, as a sociotope, as a topography of brain areas, and described purely in terms of sounds and language.

[The introductory text Eros and Violence, written especially for the booklet by Hannah Monyer, a physician and university lecturer researching in Heidelberg, offers key concepts here.

J. Marc Reichow [from the booklet]

The recordings were made in the summer of 2021 in the Protestant Church in Dilsberg (Gesualdo, Rossi), in 2007 in the Protestant Church in Mahlberg (Vivier), and in 2021 in Berlin (recitations).

In addition to the introductory text mentioned in the booklet, we are publishing an approximately 86-minute German-language conversation between Prof. Dr. Hannah Monyer, Walter Nußbaum, and J. Marc Reichow here on September 1.

Due to the detailed content index (only) displayed there, we recommend clicking on “Watch on YouTube” at the bottom left!